It seems that Hillary Clinton wants to tax big oil, but only on their record profits. She would do this to make up the revenue lost while putting the federal gas tax on hold for a while. While I’m sure this is more of a ploy to pander to voters due to her faltering campaign, the whole thing is incredibly superficial for a couple of reasons.

The first is that taxing big oil is only going to shift the cost to consumers. While you might see a temporary drop in prices at the pump, businesses typically shift such burdens on to the consumers. Doing this only makes sense for their bottom line. Beyond this, it will cause an increase in demand, causing prices to rise naturally. But then, Hillary apparently doesn’t care what economists think.

Secondly, there’s the temporary nature of the repeal. Reinstating the tax after it’s been rolled back for a while will be unpopular on an epic scale, but I suppose Hillary is mostly going for a short-term boost to get her through to the November elections. Naturally, I’ve heard nothing about rolling back the tax on big oil’s profits once the federal gas tax would go back into effect. That means that the consumer is going to be doubly hurt in the end anyway.

This leaves big oil’s profits right where they’re at now. Taxing big oil’s profits isn’t the answer — and neither is breaking up the oil monopolies. (Though the latter might not be a bad first step.)

The real problem is that demand has exceeded supply. This is a result of the American way of life. We depend on oil for literally everything: we are a spread out nation of roads where a child’s first thought of freedom = getting their drivers’ license, and whose development has, for generations, been driven by cheap oil. Every aspect of our lives is controlled by the road: everything from our food to our consumer goods arrives via truck. Auto companies have been complicit as well, and in some cases actively undermined attempts to create efficient mass transit systems that were a direct threat to their business model.

This isn’t a problem that can be fixed overnight, nor is it a problem that will be cheap or easy to fix. Comparisons to European nations and Japan with their comprehensive mass transit systems are inherently flawed because of the US’s relatively low population density and sheer size of our country. While effective, efficient mass transit is certainly the answer in urban and larger suburban areas, those systems do not scale well in more rural areas.

In that respect, we will always be a nation of cars — or other personal transport devices[1]. The mantra that we need freedom from foreign oil is trite, and it misses part of the point: we need freedom from petroleum in general, inasmuch as that is economically and techonologically possible. We will always be somewhat dependent on combustible fuels so long as the internal combustion engine is our primary mode of getting from Point A to Point B. (And really, aside from bicycles and our feet, there’s nothing out there that’s as efficient from top to bottom as a modern internal combustion engine.)

So in that respect, even if Hillary’s plan had a prayer of a chance of long-term success, and if she had any ability to get it passed — which she doesn’t because it’s an idea for this summer, not after January — it would be like prescribing a pain med instead of removing the thorn from one’s foot.

The proposal is just astonishingly dumb on every conceivable level.

I do have some related thoughts about the next ten years…

1) We’ll see a small resurgence of the railroad industry. Rail travel is more efficient than air travel, and solves some of the mass transport problems presented by our spread-out nation. This will resemble the current hub-and-spoke airline system in the short term. Business travelers won’t mind taking the train as much due to the ubiquity of wireless internet access and the fact that you can use cellphones while on a train. Trains don’t have to be slow, either. So while you won’t be taking the train from NYC to LA for a one-day affair, you might well take it from Boston to Washington DC for the same.

2) More effective car-pooling systems. Thanks to the Internet, it’s easier to more effectively carpool with folks headed in your direction. This could be supplemented by mass transit systems — buses in the beginning, and trains later on — where people gather at smaller, de-centralized staging areas for a trip into the city. Many suburban areas already have these systems, but there are many, many larger cities that don’t.

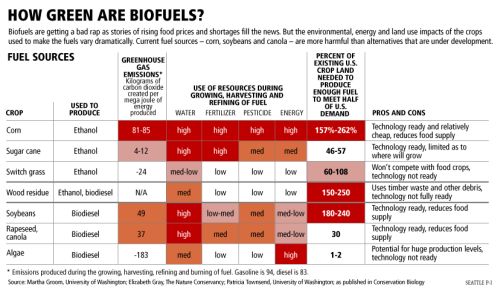

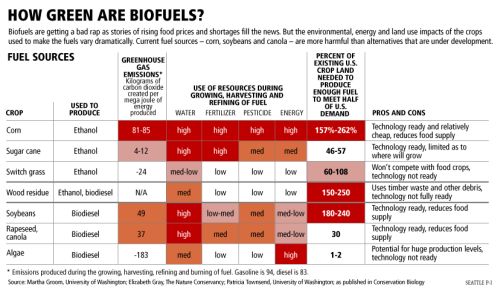

3) More and better research into biofuels as a replacement for traditional petroleum. This goes beyond corn-based ethanol which was a failure of epic proportions, as it resulted in increased food prices and is energy-intensive to produce. The graphic below (click for larger) demonstrates some of the more promising alternatives, particularly algae and switch grass.

(Preserved against link-rot from this article.)

I think America is getting to the point where they’re ready to think about letting go of their precious four-wheeled transportation. Drive by a used car dealership, and you’re likely to see quite a few gas guzzlers sitting on the lot. This alone is anecdotal evidence that the PED of gasoline isn’t zero. A more formal study finds that when the price of fuel goes up and stays up by 10%, the process of adjustment is dynamic and far reaching:

- The volume of traffic will go down by roundly 1% within about a year, building up to a reduction of about 3% in the longer run (about five years or so).

- The volume of fuel consumed will go down by about 2.5% within a year, building up to a reduction of over 6% in the longer run.

The reason why fuel consumed goes down by more than the volume of traffic, is probably because price increases trigger more efficient use of fuel (by a combination of technical improvements to vehicles, more fuel conserving driving styles, and driving in easier traffic conditions). So further consequences of the same price increase are:

- Efficiency of use of fuel goes up by about 1.5% within a year, and around 4% in the longer run.

- The total number of vehicles owned goes down by less than 1% in the short run, and 2.5% in the longer run.

Prices have certainly gone up by more than 10% in the last 12 months, and the snowballing effect of this phenomenon is that many people of my generation have gotten rid of their cars where and whenever possible, and instead opt for healthier, less expensive modes of transportation: walking or biking. When they need to travel a longer distance, they rent a Zipcar.

I certainly would if it were realistic.

[1] I could see motorbikes becoming more popular, as they are in the UK, as gasoline prices continue to rise. For Americans who have not been to the UK, it is not uncommon to see motorcycles and scooters out and about, even in the rain.