I will have a large writeup on real, honest-to-God ways we can reform healthcare in this country without resorting to re-distributionist tactics in the next couple of days. No hand-waving. No pie-in-the-sky. I promise. But until then…

By Frank Micciche from the New America Foundation/Providence Journal:

439,000 people have acquired health insurance since the reform became law — an astonishing 9 percent increase in coverage at a time when the national rate increased by one-half of 1 percent.

Nearly 200,000 of the newly insured acquired private, unsubsidized coverage, mostly through their employers.

Written another way: “More than half of the individuals are subsidized with taxpayer money.”

Libertarians will have a field day with the other piece of puzzle: many individuals would rather pay the fine associated with forgoing the mandatory medical insurance than pay the premiums. Why? The fine costs less. Many healthy people simply don’t want to buy health insurance. The original projections for the number of unsubsidized signups ended up being wildly optimistic:

Massachusetts’ financing challenge emerges from its success in covering the state’s neediest residents. Enrollment in the fully subsidized Commonwealth Care program has been higher than expected, while enrollment in the unsubsidized Commonwealth Choice plans has been lower than anticipated. Therefore, costs to the state have risen dramatically.

Micciche spins it another way:

The state’s success enrolling lower-income households in the subsidized “Commonwealth Care” program has driven overall costs above original projections, but the actual cost per person covered is lower than expected, as is the average premium.

From an economic standpoint, enrolling lots of lower-income households is not success unless it is offset by sufficient numbers of unsubsidized enrollees.

Obviously it follows that the average premium is lower than anticipated because the majority of enrollees are subsidized and therefore pay lower premiums.

This isn’t rocket science econometrics, folks.

In the fiscal year before passage of health-care reform, Massachusetts spent $710 million to reimburse hospitals and community health centers for unpaid bills. 81 percent of these costs were incurred by individuals without insurance.

Now we spend that money getting these people the insurance they need so when they go to the ED, they aren’t “uninsured”. Instead we buy these people insurance with taxpayer money so we don’t have to spend taxpayer money reimbursing hospitals directly.

What’s not mentioned is that this is good for the hospitals. A lot of “free care” ends up not being reimbursed at all, meaning hospitals have to eat the costs of treating those who cannot afford to pay. The upside for hospitals is that now that these folks have insurance — subsidized though it may be — hospitals can get reimbursed for services they provide that wouldn’t have been reimbursed in the past. It will be interesting to see if there’s an effect on the number of hospital closures and bankruptcies going forward from here.

Costs aside, all agree that sporadic treatment of the uninsured through emergency rooms and clinics is much less effective medically. The commonwealth took on the problem by diverting much of its uncompensated care pool dollars into subsidies to buy private insurance by lower-income individuals and families. Quarterly costs for free care have subsequently dropped 40 percent.

From one money hole to the next. Yes, that has “sustainability” written all over it. Payments to hospitals have dropped by 40%, and that’s a good thing. Except that that money went to the Commonwealth Care program instead. Instead of being red ink in one set of books, it’s red ink in another.

Clearly there’s a difference between red ink and politically-acceptable red ink. At the end of the day, though, the same people end up paying the piper:

The subsidized insurance program at the heart of the state’s healthcare initiative is expected to roughly double in size and expense over the next three years – an unexpected level of growth that could cost state taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars or force the state to scale back its ambitions.

State projections obtained by the Globe show the program reaching 342,000 people and $1.35 billion in annual expenses by June 2011. Those figures would far outstrip the original plans for the Commonwealth Care program, largely because state officials underestimated the number of uninsured residents.

Back to Micciche:

And the individuals who acquired private insurance now receive coordinated, cost-effective care that will improve overall health outcomes and reduce the need for more expensive late-stage intervention.

An oversimplification. Many of the patients that are now insured — both subsidized and unsubsidized — cannot find primary care physicians because the program didn’t even attempt to solve one of the major problems with healthcare today: there aren’t enough practicing primary care physicians to handle the influx of new patients. Why? Because being a PCP isn’t a financially attractive proposition. Attempts to alter the landscape of our medical system are continually undercut by talk of reducing Medicare reimbursements to primary care physicians — the very people who will bear the brunt of that manufactured demand. This, in turn, sends the wrong signals to medical students weighing a career in primary care as opposed to a more lucrative specialty.

This dearth of PCPs isn’t unique to Massachusetts, either.

Look, I’m all for increased access to healthcare when it makes sense, and I don’t think ED overusage and overcrowding is sustainable or desirable. I know that health outcomes are worse when non-emergent cases are seen in the ED. ED care is also inherently more expensive. In short, you get less bang for more bucks — and it potentially endangers those who are at the ED for real emergencies by diverting the limited resources to non-urgent cases.

I would like to think that everyone in this country can have their own primary care doctor, but I know that our infrastructure cannot support it. I am not a Darwinian capitalist. I don’t hate poor people. But I do know what is sustainable and what isn’t.

It worries me that if the nation looks to Massachusetts as some kind of prototypical model to be copied, we’re going to be manufacturing big problems, because coverage is only a superficial issue.

Healthcare coverage is not the same thing as healthcare access, even though it is politically expedient to conflate the two concepts.

Universal health coverage will manufacture healthcare demand in dramatic fashion, and the existing healthcare infrastructure isn’t equipped to deal with the kind of patient influx that that kind of universal program would create. We don’t have the human capital to meet that demand. We need to work on our healthcare infrastructure before we dump millions of new patients into the system overnight.

—

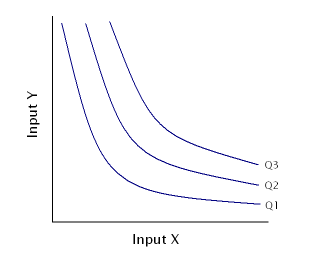

The most interesting thing that strikes me when you look at these numbers is what they say about real demand. Demand for universal health coverage by those that can afford to pay for it is less than our models predict. Even by making health insurance mandatory and enforcing it with a fine, many people are still opting out; they find that their money is better spent in other ways.

Maybe we need to revisit our models and (certainly) our cost projections.