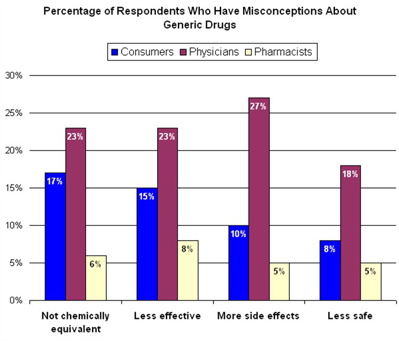

And both groups rank below pharmacists by a large margin.

I think this graph is very telling. (Thanks to John Mack from Pharma Marketing Blog.) Click it for a larger image.

The results are from Medco’s 2006 Drug Trend Report. As one of the largest PBMs in the country, Medco is in a unique position publish statistical analysis of drug trends because their subscribers are from every conceivable demographic.

“The survey found that physicians trail consumers and pharmacists regarding their knowledge of and confidence in the safety and effectiveness of generic drugs which could have broad implications for the forthcoming boon in savings from the expected drug patent expirations of branded drugs worth over $40 billion in U.S. sales:

- “One quarter of the physicians surveyed stated that they do not believe generic medications to be chemically identical to their branded counterparts; more than 8 percent said they were unsure. This despite FDA rules that require generic versions of the drug be bioequivalent to the brand medication

- Nearly one in five physicians believes generic drugs are less safe than brand-name medications, and more than one in four doctors (27 percent) believe generic medications will cause more side effects than brands”

Just wonderful. It’s true there are slight differences between brand and generics. Dyes, binders, and disintegrants may be slightly different, but these differences are usually negligible, to say nothing of potential side effects. After all, who is to say that the brand name drug’s binders, disintegrants, and dyes are less likely to cause problems than the generic equivalent’s? Answer: impossible to know without trying. Doh!

Now seems like a good time to link up my generic drug FAQ post.

When discussing generic drugs with patients at the pharmacy, they often want to “talk to their doctor” about it. I’ve known for a while that doctors are less educated than pharmacists when it comes to brand vs generic drugs.

Sometimes it wears on me — in chain pharmacies, individual pharmacies within the chain are measured by many things, one of them being generic conversion rates — and I’ll go out of my way to convince a particularly adamant patient to switch.

Take for instance, Celexa. We carry the Inwood brand generic which is the “authorized” generic. It’s actually made by Forest, and the Inwood bottle even says it’s made by Forest. I showed the patient the tablets (virtually identical, the numbering was slightly different), showed her the bottle (“See? They’re both made by Forest.”) and I still got the same response: “I’ll talk to my doctor first.”

It can be very frustrating when it comes to things like these because it costs the patient money, and the insurance company money. The only people who win are the big pharmaceutical manufacturers. In the case of Forest, they’re making about twice as much money simply because she refused to switch to the identical generic. (And she paid $25 more out of her own pocket.) It’s nice to see statistical data that corroborates what most pharmacy personnel already know: doctors aren’t the best source of information when it comes to generic drugs.

[tags]Medicine, pharmacy, consumers, doctors, generic drugs[/tags]

An Improvement to a Flawed System

More now than in the past, generic medications have been encouraged by prescribers at a much higher rate due to the problem of the high cost of branded meds that many find unfair and unreasonable. Branded meds are still prescribed often, though, mainly due to samples of such meds provided at a doctor’s office from the sales reps who promote these meds. Generics typically are not sampled due to lack of funds compared with branded pharmaceutical companies. Yet generics cost a small fraction, such as a third of the cost, of the same branded meds that have the same molecular bioequivalence. Yet not all branded meds have a generic formulation due to patent exclusivity and therefore cannot be produced until the expiration of this patent of the branded med. This is further complicated by possibly a degree of apathy with health care providers, who appear largely demoralized with aspects of the U.S. Health Care System. More likely, however, is that samples do, in fact, help out the patients.

Not long ago, generic meds were not prescribed that often, or produced to a great degree because of the cost of bringing such a med to the market, which at the time required the same protocols as branded meds. Fast forward to 1984, when the Hatch-Waxman Act was introduced, and this Act only required generic meds to demonstrate bioequivalence to the branded med that they desire to reverse engineer, and nothing else included in the approval process. The reduced cost of generic production allowed for more of these meds to saturate the market, and doctors started prescribing more generic meds as a result. Branded pharmaceutical companies were not pleased in large part with this new act, so they devised schemes to extent the patents of their branded meds, through such tactics as reformulation, which is called Evergreening, of their meds and frivolous patent infringement lawsuits, which delay generic availability for a longer period. Yet pharmacies support generic use, as they make more money off of generics compared with branded meds. So delays will not prevent the utilization of generics, overall. Generics seem to remain a concern to branded companies in spite of their efforts of avoiding their access, as branded companies have progressively started producing their own generic meds along with their branded ones due to the increased use of generics.

Also, other reasons for increased generic prescribing is due to the awareness and clinical experience of the previous branded med that has been replicated by the generic med. Newer drugs at times are not a desirable choice of treatment for patients because of lack of confidence- safety being the main concern with some prescribers. So the familiarity of a generic equivalent of a known med creates a more reassuring choice for the prescriber. Available generics are listed in what is called an orange book. It should be available to all health care providers for their access.

Most encouraging for even greater use of generic meds is that at least one company has created vending devices for doctor’s offices for dispensing both generic and over the counter meds. This may discourage the use of branded equivalent meds at a greater amount with generic samples available as well as the branded meds. In addition, and in some cases, doctors can order generic samples from the manufacturers. Knowledge is a good thing.

Yet some doctors insist that you get what you pay for, so they are convinced that branded meds are always more efficacious and tolerable than generic meds. This misconception is a fallacy, since both forms are identical from a bioequivalence and bioavailability paradigm, as required for approval. I’m sure it’s possible others have encouraged such doctors to take such a stance void of fact and reason. Yet there may be some truth to decreased efficacy of generic meds over their branded equivalents.

Considering the health care crisis in our country and the over-priced treatment methods in our system, as with branded pharmaceuticals, generic medications should be considered when clinically appropriate for the benefit of those seeking restoration of their health. It would beneficial for patients to become aware of this pharmaceutical system and request generics when being prescribed a med by their health care provider. In other words, they should question authority figures such as doctors are perceived to be, as patients definitely have a right to acquire knowledge and use this for their benefit with situations as their choices for treatment options, as this will be for their financial benefits while improving their well-being with generic medications- an ideal way to reduce health care costs and improve compliance with their meds because generics are an affordable asset to public health.

“What good fortune for those in power that the people do not think.†— Adolph Hitler

Dan Abshear