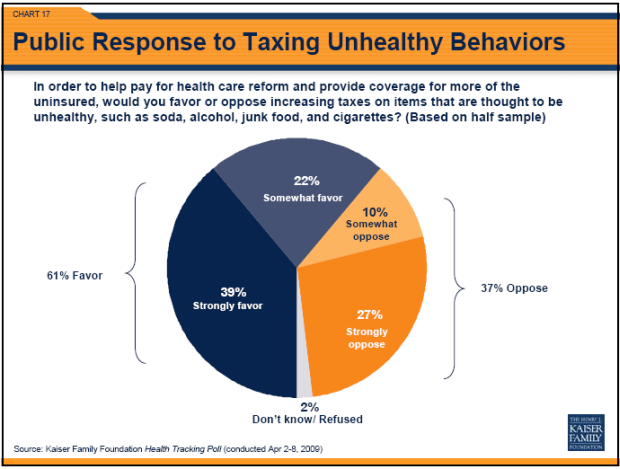

The Center for Science in the Public Interest — an organization I’ve wanted to work for — is pondering a soda tax. It’s not a new plan… I first had the idea in the fall of last year, though I didn’t write about it, and Ezra Klein has written about it twice. (1, 2) Quite a few people in a Kaiser Family Foundation/NPR poll (PDF) are in favor of it as well:

I don’t see a problem with it, really. It’s not a bad idea to take the negative externalities associated with a given activity and force the market to internalize them. I have a paper sitting on my hard drive that I’ve been meaning to adapt for the web for a while, but I’ll share a snippet here:

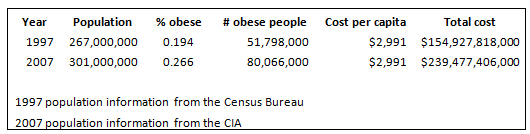

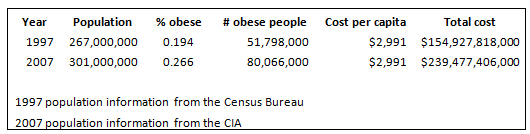

Money that would have greater marginal utility upstream is instead being spent downstream, because measuring the downstream effects are easier than measuring upstream effects. We spent an estimated $91.3 billion in diabetes care in 2002. How much money could be saved not just in diabetes but on healthcare in general if we combated the upstream problem of obesity instead of throwing money at its downstream consequences? Drastic expenditures on things like adverse cardiovascular events? In 1995, the economic cost of obesity was estimated at $99.2 billion. In 1997, an estimated 19.4% of the US population was obese (PDF). In 2007, that number jumped to 26.6% (PDF). Converting 1995 dollars to 2007 dollars, assuming that real per capita obesity costs did not increase over time (very unlikely) gives us this chart:

Obesity is probably the main public health concern in the United States these days. Communicable diseases have largely been eliminated through public health efforts, leaving lifestyle diseases as the main cause of morbidity in this country. If we cut our obesity rates in half, we could eliminate quite a lot of spending further down the line.

That adds up to about $240 billion a year spent on obesity care.

Pigouvian taxes work. By making the market account for the negative effects of its activity, it modifies consumer behavior — if not on an individual level, then certainly on a macro level. A 3 cent tax on soda doesn’t sound like much, but I’d put a significant chunk of change on it having a measurable effect on obesity. Of course it would only be one step in a real comprehensive public health strategy, but certainly not a bad step.

Before we go taxing soda, however, I would also humbly suggest that we get rid of the corn subsidies that make high fructose corn syrup so cheap, and eliminate sugar tariffs as well. Not that sugar is any healthier than HFCS from a public health standpoint, but it’s not generally good policy to layer a tax on an already-distorted market. If we stopped subsidizing corn production, we might not even need to have a soda tax… the increase in price might well take care of the over-consumption problem by itself.