March 22, 2015

This article is for people who have defaulted on their Sallie Mae/Navient student loans. If you haven’t defaulted, or if you’re paying traditional subsidized or unsubsidized federal loans, this won’t work for you. For those of you that ARE in this position, this post is for you. You can get your life back.

I’m sharing all of my actual numbers, because it makes the conversation more useful.

Managing the chaos

Like many people, I was unemployed in 2009-2010. I had the bad fortune of graduating in the middle of the recession, and had quite a bit of difficulty finding a “big kid” job, i.e. one that would let me pay my bills–including my student loans. Also like many people who are struggling with debt they can’t pay, I was plagued by phone calls, and they were universally unproductive, because stones don’t have much blood to give. The first step to getting your feet under you is to create mental space, and the biggest thing is to stop the unwanted calls.

In addition to sending letters, I did this:

- Get a Google Voice number

- Log into your delinquent accounts, and use the Google Voice number as your only phone number

- Don’t answer numbers you don’t recognize

- Take down each collection agency’s contact information (phone number, debt they’re collecting on, etc.) when they leave you a voicemail

- Block each caller one by one

This builds a strategic rolodex for tackling your debts when you’ve got your feet under you. If getting back on your feet takes a while–it took me 2 years–you’ll notice that debt gets resold fairly often, and as it gets resold, the settlement offers get better and better. This is particularly true for unsecured, consumer debt, and less true with student debt.

Negotiating with Sallie Mae/Navient and FMS

Sallie Mae stops trying to collect debts themselves fairly quickly, and they tend to outsource this to other agencies. Unlike consumer debt, Sallie Mae does not sell the debt to the servicing organization. Instead they retain ownership of the debt, as well as the terms and conditions under which that debt may be settled. (In fact, if you try to call Sallie Mae directly, you will be redirected to the servicing agency without ever having talked to a human being.) The debt collector is just a proxy, but they’re the ones you’ll be dealing with.

My debt was serviced by an organization called FMS. You can Google them; there are many horror stories, but my experience was pretty good, barring a few incidents. I had settled a couple of smaller credit card debts to this point, so I made sure to unblock their phone number only when I had a small lump of money available to make a down payment. I knew I wasn’t going to be able to discuss a full settlement, but maybe I could do something to move the needle in the right direction. This ended up being a good move, though the benefits weren’t obvious until much later.

Default settlements

I’m going to use the term “default settlement” below. I don’t know for sure, but I believe that Sallie Mae’s proxies are authorized to offer some percentage (65-70% or so) as a settlement amount, without phoning the Sallie Mae mothership. The reason I believe this is true, is because they would periodically offer me settlements on the spot which didn’t require them to phone home. This was in contrast to my counteroffers which required a ~24-48 hour turnaround time where they had to talk to someone with more authority.

The reduced-interest plan

June 2011 balance: $144,586.

I brought my account up to date on July 25, 2011 with a $1,493.38 payment, and set up a recurring payment every two weeks for $372.56. This was their “reduced interest plan”, where the interest rate dropped to 0.01%. There was no discussion of a settlement at this point that I can recall. If there had been, it would have been WAY more money than I had, so it didn’t matter.

I made bi-weekly payments from July 2011 to May 2012.

The first settlement offer: the first $80K

In May 2012, I got a phone call from FMS to re-up my recurring payments. (They can only schedule 12 at a time.) At this time, the rep I had been dealing with all along offered me a settlement that was still too large for me to take advantage of in one shot. I told her as much, and if I recall correctly, she conferred with her manager and the Sallie Mae mothership, and they made me a counter-offer: an $80,000 reduction if I:

- Made a $7000 down payment by the end of the month

- Paid $800/month for 45 months

- At the 0.01% interest rate

This dropped the loan term from 155 months to 45 months, a 9+ year reduction. BUT, if I broke the terms, the full balance came back at the original interest rate, minus whatever I’d paid. I went for it, because saving $80,000 and 9 years was too good to leave on the table.

- Settlement starting balance: $45,375

- Made the $7000 down-payment (with my dad’s help) in May 2012, which

- Reduced the amount left to pay to $36,375 (or so I thought, more on that below)

I set up a $400 recurring payment every 2 weeks, including months with 3 weeks to ensure I’d make the deadline with some headroom.

A bump in the road

Unfortunately, FMS wouldn’t send me paperwork stating the terms of the settlement, which (as I suspected) came back to bite me. I also hadn’t recorded our phone conversations, because until this point, there was no reason to think that I would need to.

December 2013 rolled around, and I received a phone call telling me that I was almost out of time, and that I owed like $45,442 by ~February 2014, which didn’t sound right. Unfortunately, I was dealing with a new representative, and she couldn’t decipher the notes of the previous representative. It was my notes against theirs… and when you’re in this position, the other party holds all the cards; you’re just along for the ride, hoping they don’t fuck anything up too badly. (That said, I’m very confident that my notes were more accurate. Not that it mattered then, and I can’t imagine it would have mattered in a courtroom.)

There was about a week of back-and-forth, but the takeaway was that I owed the $45.4K, but that the terms were extended until September 20, 2018. That was a big relief–there was no way my pre-wife and I could have come up with the money in that time.

I made sure to record that conversation should things go awry again. Check the laws in your state… my state is a two-party state which means that I needed the rep’s permission to record the conversation.

The final $20K

Because FMS can’t schedule more than 12 payments at a time, I end up talking to them about once a year. While re-upping my payments for this year, the rep mentioned that for whatever reason, Sallie Mae was accepting settlements “for pennies on the dollar this month”. That’s just a figure of speech, so I didn’t know if that was literally pennies or what, but she asked if I was interested in seeing if they would re-negotiate the settlement, because I’d basically paid $35K already, and was a model citizen. Of course I said yes, and they offered me their default settlement of $24K on the $35K owed on the spot, which is 68 cents on the dollar. I told them I couldn’t do more than $10K–a true statement–fully expecting a counteroffer for somewhere between $10-20K, whereupon we’d have to borrow some money from my wife’s parents. They said they’d have to call SLMA to see if they’d approve it.

The next morning, I got a call back: Sallie Mae had approved the $10K for the remaining $35K. The rep was shocked. The manager was shocked. They told me no one in the office had thought it would go through, which I believe. I get the feeling I’m going to be an office legend for the foreseeable future.

Recap

- $144,586 original balance

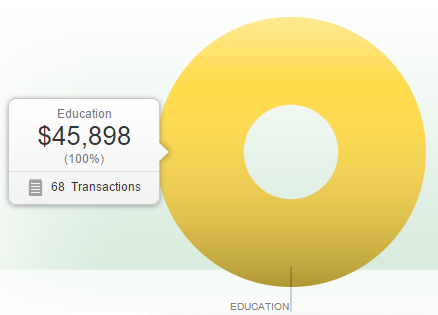

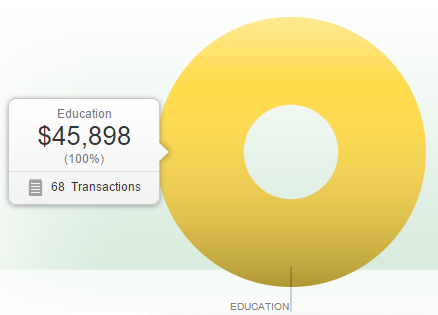

- $45,898 paid over 3.25 years

- $98,688 saved

- 68% discount (or 32 cents on the dollar) when all was said and done

FMS payments

Here’s a Google spreadsheet that shows all the debits over that time. Alternatively, you can download the Excel version.

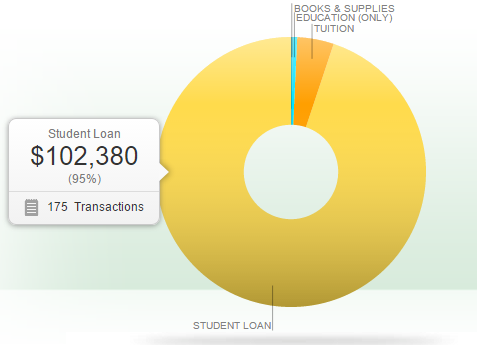

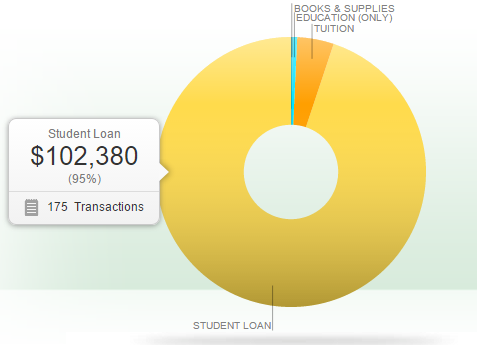

Total student loans paid during this time

I have more traditional subsidized and unsubsidized student loans that actually had interest rates, so I focused on overpaying those during this time.

Conclusions and tax implications

Once you wrap up your settlement, you’ll have taxes to pay. In my case, my income tax burden for 2015 is now my salary + $98,600, which is… a lot. Depending on where you are financially, you may be able to reduce the canceled debt “income” by whatever your net worth is, if it’s negative by filing a Form 982. To determine if this is available to you, you can fill out the worksheet on page 8 of this IRS form. If the sum you come up with is negative, you can subtract that amount from your paper “income”. (I suggest you talk to an accountant if this applies to you, though.)

Other options include maxing our your pre-tax retirement contributions (401k/403b), and/or using your FSA plan to do something expensive like getting the LASIK you always wanted. Unfortunately, doing this latter thing requires knowledge ahead of time that you’ll be settling during this particular FSA year.

Otherwise you’ll want to adjust your tax withholding, because you’ll pay an underpayment penalty in addition to the tax on this “income” if you don’t pay enough tax throughout the year.

So I settled on a settlement saving my wife and I about $100,000 and ten years. This will let us buy a house and start a family years earlier than we had thought we’d be able to. I think my situation may be unusual, but I don’t believe for a moment that I am a beautiful and unique snowflake. Three and a half years ago, my Sallie Mae situation seemed hopeless, and now… it’s over. It took a lot of hard work, and an unwavering focus to get here, but it can be done.

If I can do it, so can others.

Addendum – June 1, 2015

I wrote this article back on March 22 — 3.5 months ago. I had expected to be able to publish this much earlier, when I got the statement that our business was concluded. During this period, a few things happened

- I never received the paperwork stating that I had fulfilled my side of the deal

- Sallie Mae/Navient and FMS parted ways as business partners, which made it harder for me to get information from either one of them

- I had to fight with Sallie Mae/Navient in an attempt to get them to send me paperwork. They never did. When I talked to them on the phone, they stopped allowing me to record our conversations for some reason

Until today, I had no idea whether this was really done or not. I pull my credit report every year, and was expecting to wait until the summer in order to see if the status of my Sallie Mae/Navient loans were changed. But I bought a new car last week, and part of the financing involved the dealership pulling my credit report, which I was able to take a picture of. It indicated that the loans were settled for less than the balanced owed.

I feel reasonably confident that this is the end. Finally.

Leave a comment

- If it’s your first comment on my blog, it will probably go into the moderation queue. Don’t worry, it’s not lost; I just need to approve it. It could be a few minutes, hours, or days. I will get to it, though.

- Try to explain how your situation is different than people that have commented before you. Questions that amount to “I owe money, but can’t afford payments. What should I do?” aren’t constructive.

- I will assume all questions are about private loans only. Federal loans are a completely different kettle of fish.

1099-C update – Feb 2, 2016

I received ten(!) 1099-C forms from Navient on Jan 28. When I reported them on my taxes, I collapsed them down into a single entry for the total amount. I also filled out insolvency Form 982. I was deeply insolvent at the time of the discharge, so instead of paying income tax on an extra $115,282, I only paid income tax on $32,313, because I was underwater by $82,969.

I used TaxAct, which made the process very straightforward. I collapsed the ten forms into a single line item because TaxAct cannot handle more than five 1099-C forms, and their Form 982 worksheet can only be applied against a single line item. We’ll see if the IRS complains. (I don’t know why they would:- the numbers are identical whether they’re reported across ten line items or one.)

Settlement amounts from other readers